Written by Julia Zhu - UPG Physiotherapist & Pilates Instructor

People reporting symptoms such as joint pain, stiffness and swelling, mainly in hands, knees and hips might be experiencing a chronic disease and the most common form of chronic arthritis known as Osteoarthritis (OA). Although there are no specific causes, the common risk factors for OA include joint injuries, excess weight, older age, female and repetitive joint-loading tasks.

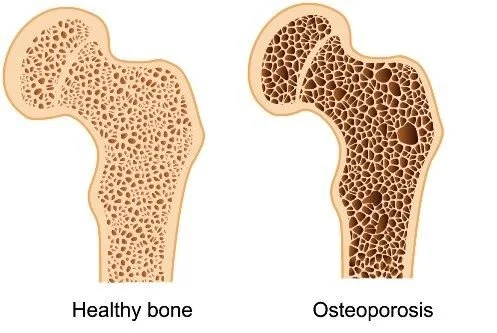

The knees are among the joints most affected by OA. It is characterised by degeneration of the knee’s articular cartilage. The damaged or missing knee cartilage can cause friction between bones and changes to bone tissue, which can cause pain. Knee OA also involves changes to the bone underneath the cartilage.

Although currently there is no cure for OA, there are many non-surgical and non-drug treatments for people who suffer from this condition.

Regular exercise:

Strong evidence shows that land-based exercise such as muscle strengthening exercise, walking and Tai-chi is highly recommended. Other options include stationary bikes and Yoga.

Dosage of strengthening training - Speak to your UPG physiotherapist for a specific plan.

People with knee OA can also attend the GLA:D® program, which is an eight-week intervention and includes education and exercise. (Evidence shows to have 26-33% improvement in mean pain intensity and 12-26% improvement in overall quality of life.)

Non-drug treatment:

Use a cane, walker, or crutches to improve mobility and balance if required.

Use heat packs or hot water bottles.

Home use transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

Manual physiotherapy as an adjunct to lifestyle management - Speak to your UPG physiotherapist for a specific plan.

If you are overweight or obese, weight management is strongly recommended to reduce joint load.

Other conditional recommendations:

Therapeutic ultrasound, knee braces and lateral heel wedge insoles for medial knee pain.

Kinesio taping

Medication:

Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in low doses for short periods.

Topical NSAIDs locally to the skin: to monitor adverse events and discontinue use if not effective.

Corticosteroid injections for short-term relief but take care with repeated injections of potential long-term harm

There are a few last alternatives that where possible should be avoid or delay such as oral and transdermal opioids, vitamin D therapies, joint space acupuncture, surgery such as arthroscopic lavage/ debridement, and cartilage repair, unless there are symptoms of locked knee.

If you have any questions or would like a complete assessment of how to begin your treatment, book here for a consultation with one of our physiotherapists who will help you manage your pain, restore function and achieve your goals.

Reference:

Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis Second edition. (2018). Retrieved 9 July 2022, from https://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/Guidelines/Musculoskeletal/guideline-for-the-management-of-knee-and-hip-oa-2nd-edition.pdf

Osteoarthritis, What is osteoarthritis? - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Retrieved 9 July 2022, from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoarthritis/contents/what-is-osteoarthritis

Information for Participants - GLA:D AU. (2022). Retrieved 9 July 2022, from https://gladaustralia.com.au/

Sports injury photo created by jcomp - www.freepik.com - https://www.freepik.com/photos/sports-injury'>